Leading Through Crisis – What Ernest Shackleton Can Teach Us About the COVID Pandemic

Tags:

Azure,

Technical Track

In January 1915, polar explorer Ernest Shackleton’s ship became trapped in ice near Antarctica. For the next two years, he kept his crew of 27 men alive on a drifting ice cap, before leading them to safety. In this article I will walk you through Shackleton’s leadership during their struggle to survive. I will also highlight some key lessons in team building and cultivating empathy that might help us navigate the current crisis we are in. As I was growing up, Ernest Shackleton was one of my childhood heroes.

My interest in historical adventures, including Shackleton's, is a natural result of my mother being a history teacher and my father (who is also my best friend) an eager sailor. Today I want to focus on Shackleton’s leadership traits that are particularly relevant to our pandemic times.

In January 1915, polar explorer Ernest Shackleton’s ship became trapped in ice near Antarctica. For the next two years, he kept his crew of 27 men alive on a drifting ice cap, before leading them to safety. In this article I will walk you through Shackleton’s leadership during their struggle to survive. I will also highlight some key lessons in team building and cultivating empathy that might help us navigate the current crisis we are in. As I was growing up, Ernest Shackleton was one of my childhood heroes.

My interest in historical adventures, including Shackleton's, is a natural result of my mother being a history teacher and my father (who is also my best friend) an eager sailor. Today I want to focus on Shackleton’s leadership traits that are particularly relevant to our pandemic times.

In 1914, Shackleton had a bold and potentially history-making goal: he and his team of 27 would be the first to walk across the continent of Antarctica. It would be the ultimate adventure in polar exploration. Unfortunately, they never made it to mainland Antarctica. After a six-day gale in January 1915, Shackleton's ship,

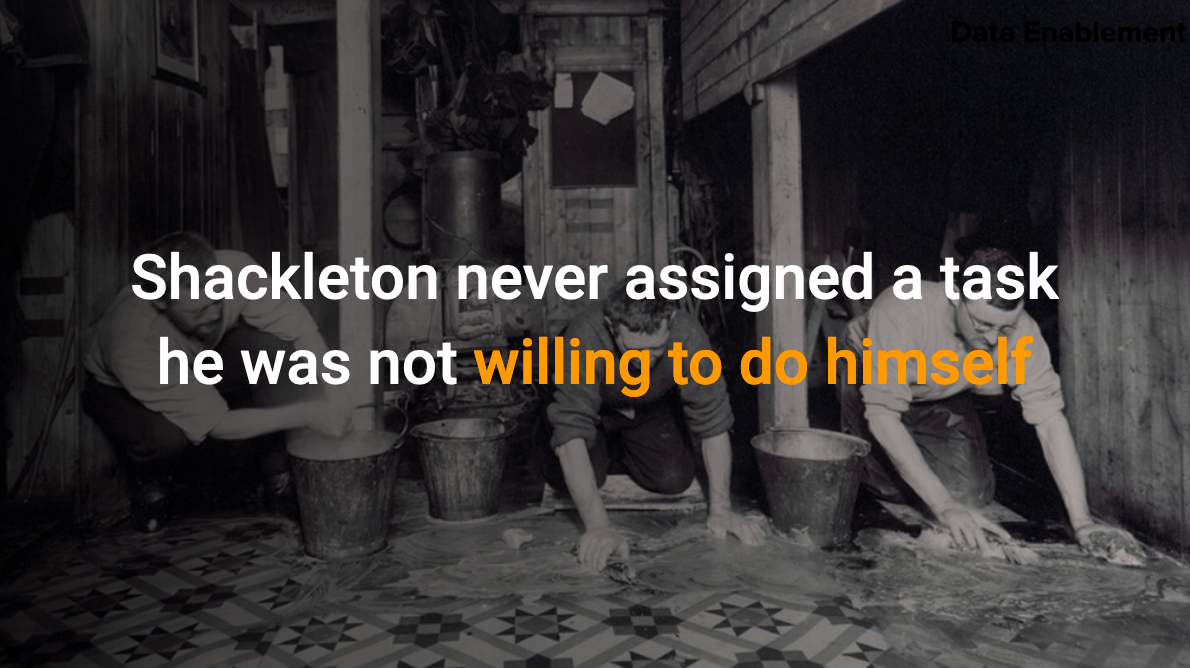

Endurance, became trapped in ice in the Weddell Sea. It would then drift stuck in the ice for ten months — with Shackleton and his men living aboard. Shackleton instinctively understood the importance of teamwork, and threw a protective cloak around his men. All were treated equally and he took particular care with anyone struggling to cope. When winter clothing was distributed, Shackleton ensured the crew was supplied before the officers. Everyone shared supplies, sailors took scientific measurements and scientists would share cleaning duties with the crew and with Shackleton himself.

In 1914, Shackleton had a bold and potentially history-making goal: he and his team of 27 would be the first to walk across the continent of Antarctica. It would be the ultimate adventure in polar exploration. Unfortunately, they never made it to mainland Antarctica. After a six-day gale in January 1915, Shackleton's ship,

Endurance, became trapped in ice in the Weddell Sea. It would then drift stuck in the ice for ten months — with Shackleton and his men living aboard. Shackleton instinctively understood the importance of teamwork, and threw a protective cloak around his men. All were treated equally and he took particular care with anyone struggling to cope. When winter clothing was distributed, Shackleton ensured the crew was supplied before the officers. Everyone shared supplies, sailors took scientific measurements and scientists would share cleaning duties with the crew and with Shackleton himself.

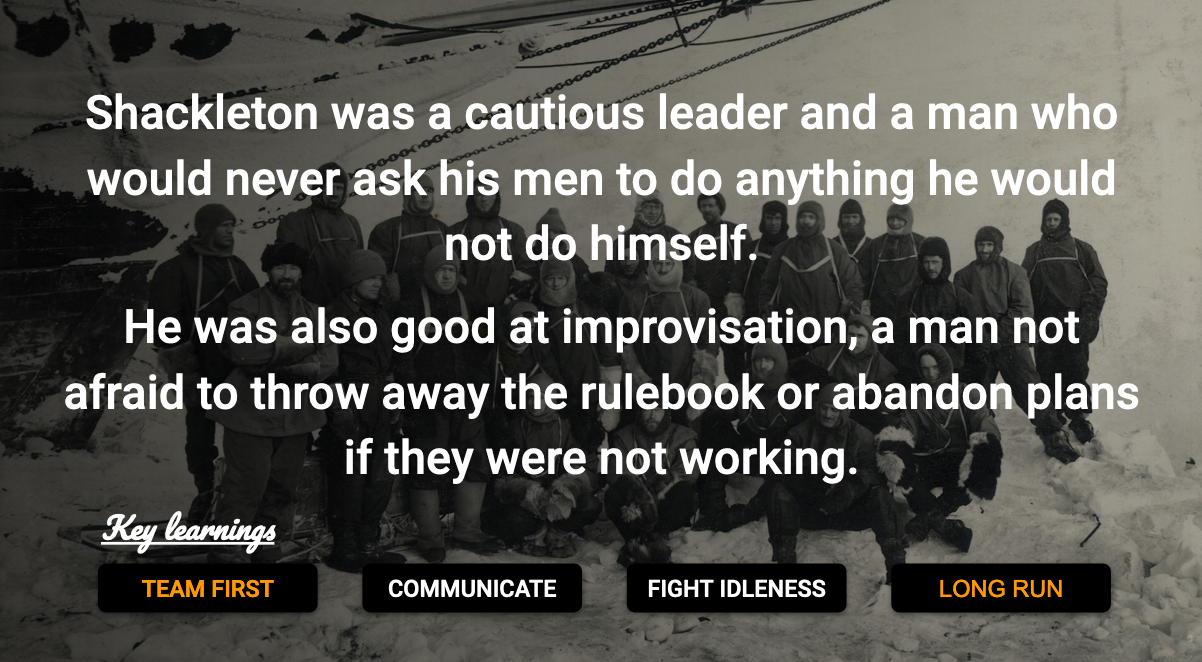

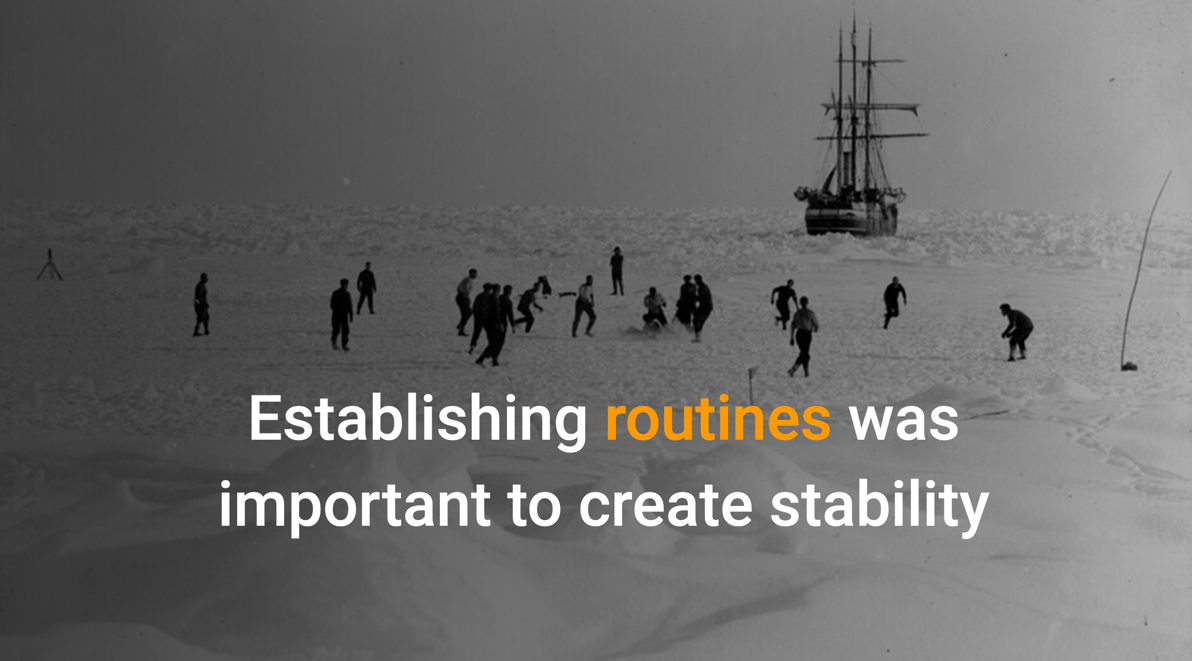

Shackleton feared the potential effects of idleness and despair among his men more than he did the ice or cold. The picture below was taken mid-February 1915, after the men had tried to release

Endurance from the ice one last time, but had to finally accept they were stuck as the cold and dark Antarctic winter approached.

Shackleton feared the potential effects of idleness and despair among his men more than he did the ice or cold. The picture below was taken mid-February 1915, after the men had tried to release

Endurance from the ice one last time, but had to finally accept they were stuck as the cold and dark Antarctic winter approached.

To maintain morale, Shackleton had the crew exercise on the ice, play soccer, and participate in indoor games. After dinner, the sleeping quarters in the hold — which they mockingly called “The Ritz” — were used to stage parties, games, and some other unusual competitions.

To maintain morale, Shackleton had the crew exercise on the ice, play soccer, and participate in indoor games. After dinner, the sleeping quarters in the hold — which they mockingly called “The Ritz” — were used to stage parties, games, and some other unusual competitions.

In April 1916, after

Endurance had finally been crushed by ice, Shackleton decided to set out in search of help. He made a dangerous 800-mile journey north using one of the lifeboats and taking three of his most experienced sailors. After almost sinking the lifeboat due to the weight of the accumulated ice, he finally reached inhabited land and in August that year was able to save all 28 men (himself included). When fame and glory called, Shackleton put his crew's safety first. On returning home from one of his first attempts to reach the South Pole, when his wife Emily asked why he had turned back with the Pole so close, Shackleton simply said: “I thought you would prefer a live donkey to a dead lion.” — an answer I always found fitting.

In April 1916, after

Endurance had finally been crushed by ice, Shackleton decided to set out in search of help. He made a dangerous 800-mile journey north using one of the lifeboats and taking three of his most experienced sailors. After almost sinking the lifeboat due to the weight of the accumulated ice, he finally reached inhabited land and in August that year was able to save all 28 men (himself included). When fame and glory called, Shackleton put his crew's safety first. On returning home from one of his first attempts to reach the South Pole, when his wife Emily asked why he had turned back with the Pole so close, Shackleton simply said: “I thought you would prefer a live donkey to a dead lion.” — an answer I always found fitting.

What are the key learnings that we can take from this?

1. Team First

If he sensed one crew member was having a rough time, Shackleton sometimes ordered a round of hot milk for everybody. This avoided singling out the man who was struggling, even if it meant consuming their precious reserves. At the same time, Shackleton was not afraid to take risks himself, like the 800-mile voyage in a 23-foot lifeboat to find help, knowing that he would need to learn his way through many uncertain situations. And that’s especially relevant today as we have to get comfortable with a lot of uncertainty and chaos, and also little and ever-changing information.2. Communication

Once Shackleton’s expedition turned into a crisis, he defined his new mission clearly — bring all his men home safely — and communicated clearly with them about what daily routines and tasks they needed to follow to achieve that goal. While that mission could never budge, he remained flexible and improvisational about how he and his team worked to attain their target, as everything from the weather to morale shifted from day-to-day. If Shackleton sensed someone was skeptical of his plans, he would invite them to stay with him in his own tent to address their concerns.3. Fight Idleness

Shackleton knew that the group's biggest challenge was not facing cold or hunger, but sustaining their spirits and creating stability. This is why he assigned duties to everybody and required all group members to exercise every day. Each night after dinner, Shackleton would meet with the crew to give them the latest updates. What can you and your team do with your “free time” that would help each other and your company, and make everybody more resilient? Be creative and proactive. Think about using the time to improve your skillset and your company processes; tools that will not only make you more resilient but more efficient in the long run.4. Long Run

Finally, working remotely invites loneliness even during the best of times. So during a crisis like our current one, isolation can become physically exhausting and emotionally depleting. I have certainly felt this myself this year. So try to carve out some personal time to recover every day because this is not a sprint, it’s a marathon.